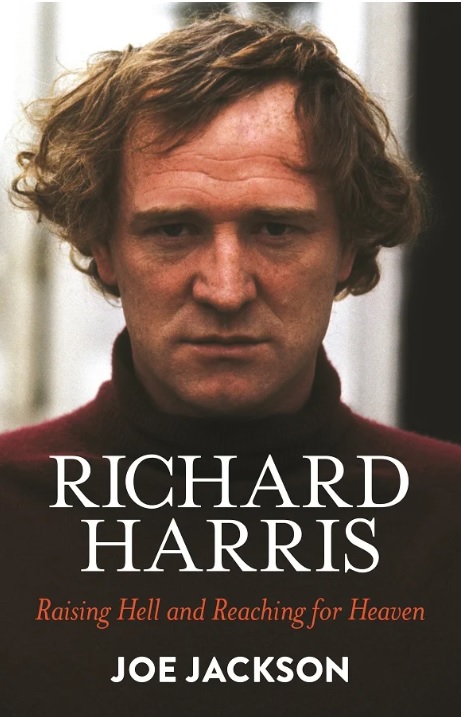

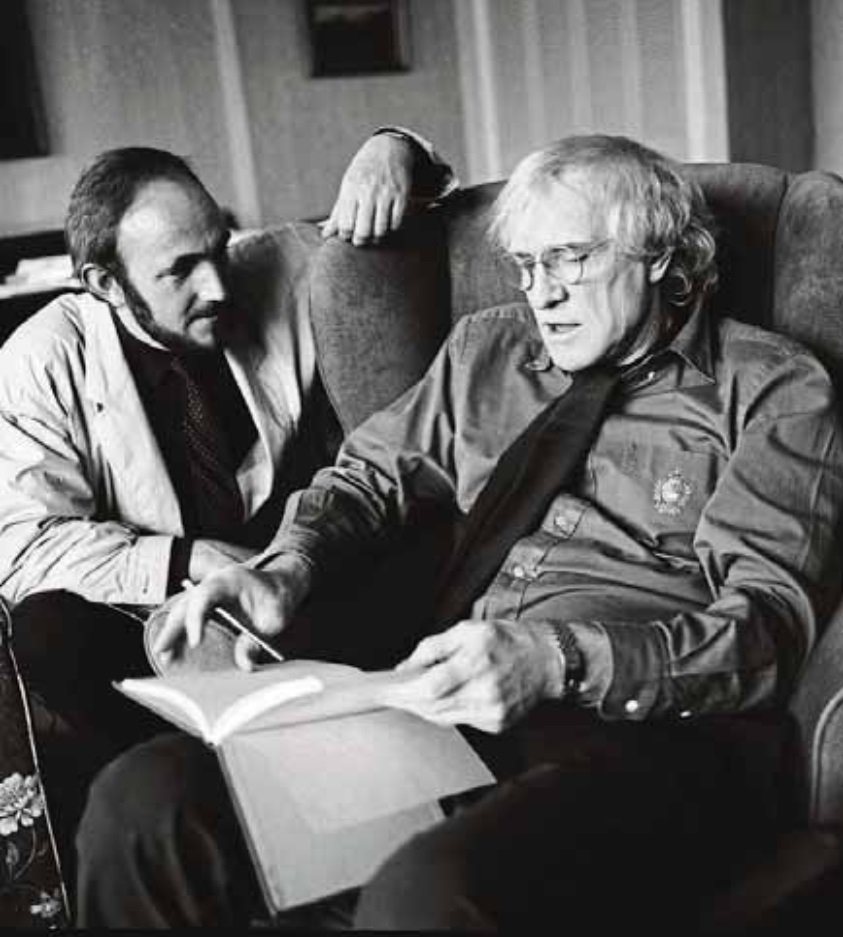

A portrait taken of Richard Harris in 1987 during one Joe Jackson's first interviews | PICTURES COURTESY OF COLM HENRY

Based on a searingly honest series of interviews that journalist Joe Jackson recorded with Richard Harris between 1987 and 2001, a new book tells the real story of one of Ireland’s greatest actors

IT WAS February 1946. The fifteen-year-old ‘Dickie Harris’ sat in a car that was part of the cortege taking the body of his beloved sister, Audrey, to the family tomb in the Saint Mount Lawrence Cemetery.

The boy couldn’t stop crying. But then he noticed something that almost brought a smile. ‘I realised that 90 per cent of the people lining the streets to pay their respects to my sister were shawlies, many of whom Audrey had helped by organising jumble sales for them, giving them her clothes and so on.’

When Richard Harris told me that story in August 2001, the word ‘shawlies’ to him, it meant ‘poor people’. And that memory came back into his mind while he, a member of the Harris clan, whose motto is ‘I will defend’, was living up to that motto by defending himself and his family name against attacks from, ‘sadly, certain people in Limerick’.

It all went back to the fact that when Frank McCourt’s misery memoir, Angela’s Ashes, was published in 1996, Richard ripped it to shreds in public and probably even physically in private. Harris hated the book. He said, for example, that it was ‘full of historical inaccuracies’. This prompted some McCourt supporters in the tribal city of Limerick to take his side.

I once heard a Limerick woman say, for example, ‘The Harrises were the Limerick elite. What would they know about poverty? They didn’t give a fiddler’s f*** about the poor.’ The latter accusation, in particular, made Richard livid. If only because, decoded, it suggests that the Harrises stood looking down from their ivory tower as the ‘peasants’ below died en masse from poverty and starvation.

‘‘That is exactly what angers me because it is so f***** untrue,’ he said in 2001.

Richard also suspected that the public stances he took against Angela’s Ashes, the book and the film, had left him ‘loved and loathed in equal measure in Limerick’.

And that this might be how things would remain after he was reduced to ashes. That’s why he wanted to ‘put on the record’ with me his ‘final statement’ on the subject.

But first, let me say something about the storytelling skills of Richard Harris. He described the following story as ‘amazing’. Other times, Richard would preface a similar tale by saying it was ‘fantastic’. Both were much the same thing to Harris and must be seen in the context of his previously quoted assertion that ‘truth can be dull’.

Put another way, one could say that the man who played the Bull McCabe in The Field could be full of bull. He certainly had a flexible attitude toward facts. His stories could be true, false, or fall somewhere in between, like a drunk miscalculating the space between two stools in a pub. Some say that’s where he learned his trade as a storyteller – in Limerick pubs, at a bar, or flat on his arse, laughing after falling between two stools. Or he can be seen as a seanchaí.

‘I’ll tell you an amazing story about my family,’ Harris said, telling this tale, not in a pub but in his suite at London’s Savoy Hotel. Thankfully, RH brought Ireland wherever he went and could make even a location as ‘posh’ as the Savoy seem like a pub in Limerick. My family was Protestant, originally, right? They came from Wales in 1774 and settled in Waterford. Then, my great-great-grandfather, James Harris, moved to Limerick. And he not only started our family business as millers, but he also gave to the Jesuits, free, the building that is now Crescent College!

Yet, once, when an American journalist went there to research an article about me, he was told, “We’d prefer if you didn’t mention Mr Harris in relation to this school.” They wanted nothing to do with me because of my reputation! Can you believe it? And we gave them the f****** building!

But there is more! The Harrises were, as I say, Protestant. And they retained their religion up to the time of James Harris, who married Mary O’Meehan, a diehard Catholic. And even though James Harris remained Protestant, his three children, including Richard Harris, after whom I am named, became Catholics. Then Richard Harris married a Protestant called Anderson from Edinburgh, and she refused to convert to Catholicism! The Bishop of Limerick [Bishop John Ryan] didn’t want Richard Harris to marry a Protestant, so he cut him off from his social set!

And in penance, my grandfather gave Crescent College to the Jesuits. Not only that, for further penance, he put a church inside his house, in which the Bishop, after they became friends again, celebrated Mass every Sunday at 12 o’clock. Then, of course, he stayed for a good lunch! And my mother, when the family moved to Overdale, gave the entire contents of that chapel to the Jesuits!’

Overdale is the nineteenth-century, nine-bedroom, redbrick house on Ennis Road, where Richard St John Harris was raised as the son of Mildred and Ivan Harris.

‘But my point in telling this story is to highlight the fact that my great-great-grandparents were very wealthy people. There is no question about that. They were huge millers until Ranks [Ranks Flour Mills, a UK company] set their sights on Ireland, moved in, and killed the businesses of the little millers. So, the family wealth started to disappear during my early years. I remember great wealth and opulence when I was small and still in short trousers. But I also noticed it disappearing. And I know it was disappearing because I saw my mother, who once had servants coming out of her ears, on her knees and scrubbing the floor.’

This version of that part of the Harris family history ties in with the fact that their Limerick bakery closed within a year of Richard’s birth, and a battle began to save the family flour mill. However, Richard’s brother Noel told me in 2022 that the story about a scarcity of servants leading to their mother scrubbing floors is ‘bullshit’. He said, ‘Richard was right to say the family business slowly fell apart, but my mother always had servants, and my father always had a chauffeur-driven car. I never understood why Richard seemed to find it necessary to tell lies so often about our family being poorer than we were. But he did.’

I contacted Noel Harris, eighty-nine, because his daughter Sonia told me he was ‘really hurt down through the years’ by the ‘lies Richard told about his family. Particularly the claim that his parents didn’t love each other because their marriage was matchmade.’ But let’s get back to 2001, and Richard’s tilt on this tale.

‘That was during the 1930s, yet our reputation as monied people persisted, and I have no doubt that it still does in Limerick. Although people who could be said to have known us best will tell you that even though we had money, dwindling or otherwise, we never lost the run of ourselves. That certainly would be my memory of it. So, let me address this accusation that we were elitist. Yes, we were elitist – but with no money in the end!’

Noel Harris denies this. ‘We were always relatively well off and never broke,’ he says.

Richard continued. ‘Besides, even if we came from a large, sprawling elitist family with great riches at the start, let’s not forget that James Harris gave that Crescent College building to the Jesuits, and land, for free, to build St Flannans – the most famous school in the county Clare. And my grandfather, Richard Harris, fed starving people in Limerick. I won’t say it broke him, but they used to queue up outside our place, and he gave them free bread and flour because he was painfully aware of the poverty. In other words, we did our bit. But I never once challenged McCourt’s book in terms of the poverty in Limerick at the time. I’d be a fool to deny it. There was wicked poverty in Limerick. There was wicked poverty in every county in Ireland. All our people suffered from poverty.

Yet, now they accuse us; they say we were the elite and that, as such, we could not have known anything about poverty. Of course, we f&cking knew. Even Audrey, carrying on a family tradition, helped the poor. That’s why so many turned up at her funeral. Anyway, my argument about Frank McCourt’s f***** book was its untruthfulness. McCourt’s stories about Limerick people, some of whom are still alive, were proven to be untrue. He admits it. And when you think some Americans said Angela’s Ashes was as good as James Joyce, you want to go –’ Richard Harris, the Oscar-nominated actor, then mimicked to perfection the act of puking.

‘There wasn’t a line of poetry in the whole f&cking book, Angela’s Ashes – and we Irish love words!’

I rest his case.

This is an edited version of a chapter in Joe Jackson’s book, Richard Harris: Raising Hell and Reaching for Heaven.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.